How many times have you downloaded an app or signed up for a new website to learn a language?

You sort out jumbled letters to create words, unscramble words to make grammatical sentences, maybe even type out translations on your own. Here and there, you might match pictures to phrases: a man wearing a business suit while riding his bike will be burned into your mind as « il va travailler à vélo »

And then it comes time to speak or write about yourself, you totally blank out. As confident as you may have been as those points racked up on a language-learning game, it’s difficult to reformulate those concepts when talking about yourself.

Like most people today, my second language learning has come primarily through screens, with the occasional physical workbook purchased along the way.

Most language learning apps have speaking and listening exercises, making it a little more challenging to complete each level for deaf learners and others with communicative disabilities. Some platforms, such as DuoLingo and Babbel, allow work-arounds.

I primarily use Babbel as my go-to French learning app, and when I hit exercises asking me to listen for the word or phrase, I have two approaches: my first is to select « view hint » and treat the exercise as an « unscramble the letters » exercise.

Occasionally, I am able to listen carefully enough to isolate the word — the lessons on the main pathway have limited vocabulary introduced in each lesson in order to focus on learning grammatical rules at an easy pace. There are other categories available for users who wish to specifically target different vocabulary and grammatical categories.

It has become clear to me over time though that no matter how many lessons I can complete, there’s a limit to how much fluency one can build through an app.

Language is primarily for communication

The first thing I wondered when I began learning French was, “What spelling errors do French people most commonly make?”

I wondered this because I knew that most of my communication with the French would probably be similar to most of my communication with the Americans I run into regularly: by writing or typing!

(By the way, one I’ve learned is that the word faites is often incorrectly spelled with a circumflex, as faîtes.)

Human beings use language to communicate to one another by listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Those of us with disabilities impacting our communication are no exception.

While there are often limits to how much a deaf learner can hone her listening or speaking abilities, the core need is the same: self-expression and connecting with others. We don’t learn languages so that we can be on a leaderboard for an educational app — we learn so we can know others and be known.

For deaf individuals who communicate primarily through writing, gesture, and lipreading, these are the domains of their second language that we must focus on the most. Reading words on the screen and typing out answers is all well and good, but the way to truly ingrain new words is much more kinesthetic in nature.

Taking advantage of physicality

When I began trying to learn French as a child, it was hard for me to make anything really stick. I focused on passively reading flash cards and on-screen text, sometimes watching or listening to anything with captions.

Once I got to university, I began doing two things that changed the way I saw language learning.

The first major change I made was to shift my focus from learning by typing to learning by handwriting.

This actually started out with discovering « studyspo » online and loving the beautiful handwritten notes I saw — it was satisfying to create my own, and the length of time I spent carefully creating my notes really helped; this was a three-step process involving messy lecture notes, minimalist revised notes, and finally over-the-top pretty and colorful notes.

I started doing this in an American History class.

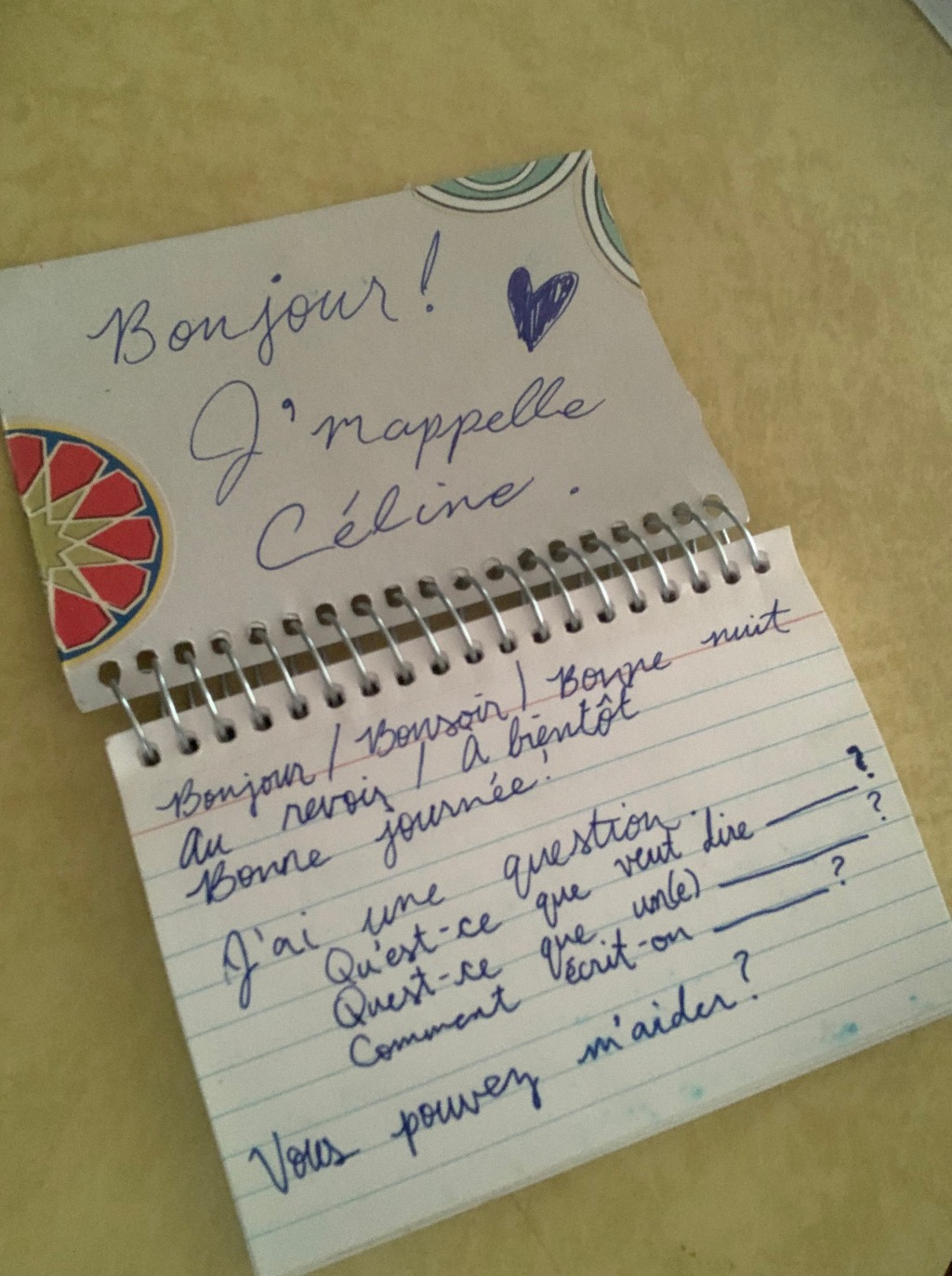

For French learning, the simple approach I had was to take all my notes in cursive, and instead of actually using my professor’s worksheets to fill in the blanks, copying the entire worksheet into my own notebooks word-for-word and filling in the blanks there.

Sounds like a lot, right?

For me, it felt as though I was drawing knowledge up from my pens and into my hands, then into my mind. It was the first step in truly retaining grammar and vocabulary — rather than writing out terminology once to create flashcards that I could read, I forced myself to constantly engage in both production and reception by always writing when I practiced reading.

The second major change tied it all together.

I found myself doing this absent-mindedly when following the advice of Benny Lewis, writer of Fluent in 3 Months. He suggests creating your own phrasebook with sentences relevant to you, and reading your phrases every day.

I wrote every short phrase I could find from different YouTube videos for anything I might ever need to express!

Being someone who tries to find humor in everything, I remember reading the sentence « Je ne jeux pas venir » and making a face as if I were breaking this harsh news to someone. I can’t make it!

Being a little over-the-top, I physically cringed and pictured a wedding, and pretended I was actively on the phone with the bride, sobbing and telling her that I — her Maid of Honor — would not be present.

I told you, I’m a liiiiiittle excessive.

Laughing, I started doing this with every sentence. I would stand up and do my best to say these phrases the way I normally would, and I would physically react. My face and body language would change, and I would utilize any French gestures I had learned.

Then I started doing this while signing the sentences as well as I could, primarily in American Sign Language. I spelled words I was trying to focus on memorizing how to spell, and I signed in a grammatical French word order. When I found an LSF-ASL app, I started translating a few signs when I could remember to.

Being a solitary learner, these two strategies helped me to internalize more of the French language. I am still a debutant, but I am finding that I learn more and more each day now that I employee these strategies of active learning.

But coming back to this… we learn languages for communication, so even with these strategies, how can deaf learners go from speaking French just to our cats to communicating with real human beings?

Accessible Resources

There are a few resources I have found most helpful, but I want to share just two here for debutants.

The one I have to mention first is iTalki, a platform for learners to connect with tutors, teachers, and conversation partners!

Most tutors on iTalki are willing to meet over Skype, Google Meet, or Zoom, all of which have live captioning capabilities. I have found Skype to be the best for this — Google Meet and Zoom have to be adjusted for captioning language, and often in debutant sessions, there is some code-switching from the native to target language here and there. The ones I have worked with are also very comfortable using the chat feature to type back and forth in the target language.

Not to mention, conversation partners and tutors often charge very low rates — having a real teacher is invaluable, but for learners on a budget, having low-cost conversations here and there can create memorable learning experiences more frequently.

I recommend when having conversations to have a physical notebook beside you, and write down sentences and new words you learn from your tutor!

For those wanting to move at a slower pace, you can’t go wrong with penpals. One of my favorites is My Language Exchange, which connects users to others around the world to help learn a new language by active conversation. This can happen through email, snail mail (my favorite!), instant messaging, or however else you want to chat.

Of course, my recommendation here is also to keep a physical written notebook as well. Typing is great, but learners should use all available methods to truly gain knowledge.

Donc…

How has handwriting played a part in your second language acquisition? If it doesn’t yet, what will you do to change that?

Leave a comment